Description and Requirements

The Book

Bibliography

Syllabus

Introduction

Introduction The Great Pyramid

The Great Pyramid Music of the Spheres

Music of the Spheres  Number Symbolism

Number Symbolism  Polygons and Tilings

Polygons and Tilings  The Platonic Solids

The Platonic Solids  Roman Architecture

Roman Architecture  Number Symbolism in the Middle Ages

Number Symbolism in the Middle Ages  The Wheel of Fortune

The Wheel of Fortune  Celestial Themes in Art

Celestial Themes in Art Origins of Perspective

Origins of Perspective  What Shape Frame?

What Shape Frame?  Piero della Francesca

Piero della Francesca  Leonardo

Leonardo  Façade measurement by Trigonometry

Façade measurement by Trigonometry  Early Twentieth Century Art

Early Twentieth Century Art  Dynamic symmetry & The Spiral

Dynamic symmetry & The Spiral  The Geometric Art of M.C. Escher

The Geometric Art of M.C. Escher  Later Twentieth Century Geometry Art

Later Twentieth Century Geometry Art  Art and the Computer

Art and the Computer  Chaos & Fractals

Chaos & Fractals

Celestial Themes

in Art & Architecture

"When he established the heavens I was there:

when he set a compass upon the face of the deep:"

Proverbs, Chapter 8 par. 27

Slide 4-38: MICHELANGELO: Creation of the Sun Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

Canaday, John. Masterpieces by Michelangelo. NY: Crown, 1979. p. 17

We will start on earth and travel upwards through the nine concentric spheres of the Ptolemaic system. We will follow the path of Dante and Beatrice in the Paradiso, looking for art motifs as we go.

The Ptolemaic system gave a geometric structure to the celestial world. In a later unit we'll see how linear perspective gave geometric structure to the terrestrial world.

God The Geometer

|

Slide 9-37: God the Geometer,

Manuscript illustration.

Clark, p. 52 |

We vowed to search heaven and earth for geometric art motifs. We'll done a pretty good job on earth, so now lets try the heavens, and what better place to start than with God creating the universe. It almost seems like Medieval man thought he laid it out with a pair of compasses, a notion which may be due to a passage from the Old Testament:

"When he established the heavens I was there:

when he set a compass upon the face of the deep:"

The Four Realms

Lets look at a Medieval version of the universe, consisting of the Four Realms that we mentioned in our unit on number symbolism. Now lets group them into two sets of two;

| Two below the moon, or sublunary: | Matter |

| Nature | |

| and two above the moon, or Translunary: | Celestial: |

| Super-celestial |

The Nine Spheres of Heaven

|

Slide 10-2: Giovanni di Paolo,

Creation of the World & Expulsion from Paradise,1445

Fisher, Sally. The Square Halo. NY: Abrams, 1995. p. 14 |

We now further divide the celestial realm into the 9 spheres of the heavens, the sun, moon, 5 planets, the fixed stars, and the primum mobile, and we get the geocentric universe shown in this picture by Giovanni di Paolo. It shows:

The Earth (brown) at center, shown as a Mappamondo, or world map, surrounded by the three other elements, water, air, and fire, its bright red clearly marks the boundary between the sublunary and translunary realms. Then comes the moon and planets, all blue, except for the Sun, yellow-white, with gilded sunburst, and Mars, in pink, for the red planet. Then the fixed stars with signs of the zodiac, the Primum mobile (the first moved) which regulated the motion of all the spheres beneath it, and the Empyrean heaven, the home of God and the angels.

The number of rings in pictures of this sort vary from one to the other. For one thing, theologians couldn't decide whether the empyrium occupied a definite sphere, or whether it was infinite and unknowable - a big problem for artists.

Di Paolo shows no ring for the Empyrium, just a region beyond the last ring, implying it can't be contained by a circular boundary.

Sacrobosco's Sphaera mundi:

|

Slide 10-7: Illustration from Sacrobosco

Dixon, Laurinda S. Giovanni di Paolo's Cosmology. Art Bull. Dec. 1985, p. 604-613. |

The probable source for di Paolo's picture and others like it was Sacrobosco's Sphaera mundi: a popular source for this information written in the 13th century and used at universities. It presented an elementary and introductory view of the universe, giving Greek cosmology with a Christian spin.

So we have what Edgerton calls the Geometrization of Heavenly Space, the counterpart of our geometritization of terrestrial space acheived with linear perspective, where all receding lines travelled obediently to a neat vanishing point at infinity. This is part of a world view ruled by a general conception of an orderly universe that God had created out of chaos, where, according to the Book of Wisdom, God had arranged all things according to Number, Weight, and Measure.

The Sublunary World

Lets take the Sphaera mundi as our road map for our journey, starting with a quick look at the sublunary realm before taking off for the cosmos.

Sublunary vs. Superlunary

Compared to the rest of the Medieval universe, our sublunary realm is not so great. We may think that earth being at the center of the is special and exalted, but things are just the opposite.

Listen to Tillyard;

. . . far from being dignified . . . the earth in the Ptolemaic system was the cesspool of the universe, the repository of its grossest dregs.. .

By the grossest dregs he probably means people.

Portrayal of Astrologers and Astronomers

|

Slide 10-101:

Bouleau, Charles. The Painter's Secret Geometry. NY: Harcourt, 1963. p. 78 |

Well, maybe we're the dregs of the universe, but we can still gaze at the heavens and wonder, and the astrologers and astronomers who do that have always been a popular art motif, as those in this medieval manuscript illustration.

Allegories to Astronomy

|

Slide 10-104: RAPHAEL, Astronomy

Edgerton, Samuel. The Heritage of Giotto's Geometry. p. 104 |

Artists also like to depict allegories to astonomy, which, we recall, is one of the Seven Liberal Arts, part of the quadrivium.

Models of the Heavens

|

Slide 10-112: Villa Farnesina

Art Bulletin, September '95, p. 421 |

|

Slide 10-114: Coronelli (1650-1718) Globes, c. 1688.

Museo Civico, Vicenza |

Here in the sublunary world we make pictures and models of the translunary world, like star maps, often painted on ceilings, celestial globes, and orreries or planiteria, little models of the solar system.

|

Slide 10-117: Orrery

Turner, Gerard. Antique Scientific Instruments. Dorset: Blandford, 1980. Fig. 10 |

Armillary Sphere

|

Slide 10-121: Armillary Sphere

Turner, Gerard. Antique Scientific Instruments. Dorset: Blandford, 1980. p. 61 |

And of course, the armillary sphere, which we saw before in Plato's Timaeus, where he describes how the circular paths for the stars were formed by the creator.

"He cut the whole fabric into two strips,which he placed crosswise at their middle points to form a shape like the letter X; he then bent the ends round in a circle and fastened them to each other . . . to make two circles, one inner and one outer."

The Dome of Heaven

|

Slide 3-6: Kepler's Model of the Universe

Lawlor, p. 106 |

Another model of the heavens is that we've seen before is Kepler's nested Platonic solids, and another is the dome. In The Dome of Heaven, Karl Lehmann, who writes,

One of the most fundamental artistic expressions of Christian thought and

emotion

is the vision of heaven depicted in painting or mosaic on domes . . .

Instruments

|

Slide 10-108:Astrolabe

Brenni, Paolo et al. Orologi e Strumenti della Collezione Beltrame. Florence: Instituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, 1996. Fig. I |

Many instruments used by astronomers, often beautifully made and ornamented, easily qualify as art objects, from this small astrolabe to these large installations in India.

|

Slide 10-107: Astronomical Sites in India

Sharma. L'Observatoire Astronomique de la Ville Rose |

Sundials

|

Slide 10-127: Sundial at Chartres

Lionass, p. 28 |

Many such instruments use shadows or shafts of light to mark the passage of time, like sundials or sun clocks, that came in all sizes, from ones you can fit into your pocket, to dials mounted on buildings.

|

Slide 10-133: Sundials Lionass, Francois. Time. NY: Orion, 1959. p. 52 |

|

Slide 10-134: Sundials Lionass, Francois. Time. NY: Orion, 1959. p. 69 |

|

Slide 10-135: Brenni, Paolo et al. Orologi e Strumenti della Collezione Beltrame. Florence: Instituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, 1996. Figure III |

|

Slide 10-136: Sundial Brenni, Paolo et al. Orologi e Strumenti della Collezione Beltrame. Florence: Instituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, 1996. p. 51 |

|

Slide 10-137: Sundial Brenni, Paolo et al. Orologi e Strumenti della Collezione Beltrame. Florence: Instituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, 1996. p. 41 |

|

Slide 10-138: Sundial Turner, Gerard. Antique Scientific Instruments. Dorset: Blandford, 1980. Figure 8 |

Sun Calendars

|

Slide 10-140: Sun Dagger

Lippard, Lucy. Overlay. NY: Pantheon, 1983. p. 76 |

Some calendars only mark particular times of the year; solstices, equinoxes, like this sun dagger in New Mexico that marks the summer soltice, or the calendar circles like Stonehenge and Castle Rigg.

|

Slide 10-141: Parma Town Hall

Calter Photo |

Other sun calendars give the approximate date by seeing where the noon mark falls on a figure called the Analemma

|

Slide 22-01: Sun Disk analemma

citation |

Another sun calendar is located in S. Petronio, Bologna, where a hole in the ceiling of the cathedral projects a shaft of sunlight onto this bronze strip on the pavement below which is engraved with the days of the year and signs of the zodiac.

|

Slide 10-143: Meridan Line. S. Petronio, Bologna

Calter Photo |

A more modern and more grim sun calendar is this Kentucky Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where the tip of the shadow of the rod falls on the names of those who died in the Vietnam war at the current date and time of day.

|

Slide 10-153: Kentucky Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Calter Photo |

Twentieth Century Astronomical Art

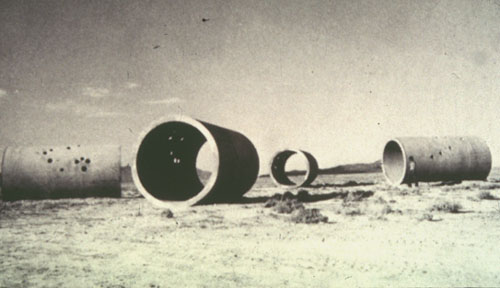

Slide 22-02: Nancy Holt, Annual Ring, 1980-91

Lippard, Lucy. Overlay. NY: Pantheon, 1983. p. 107

Slide 22-03: Robert Morris, Observatory, 1970-77

Lippard, Lucy. Overlay. NY: Pantheon, 1983. p. 110

Some twentieth century art use alignments, like Nancy Holt's Annual Ring, with openings that frame the rising and setting sun on the equinoxes, and the north star. Another is Robert Morris', Observatory, nearly 300 ft in diameter, which has slits for the solstices, equinoxes, and moonrise.

Slide 22-04: Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels, 1973-76

Lippard, Lucy. Overlay. NY: Pantheon, 1983. p. 107

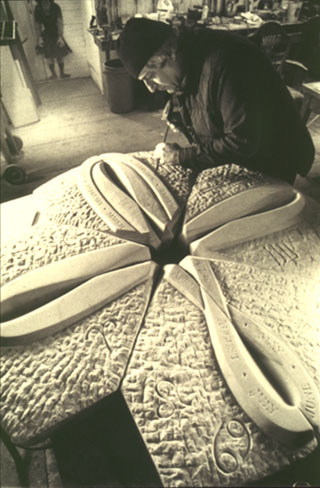

Nancy Holt's Sun Tunnels are oriented to the solstices and the holes project certain constellations on the interior dark walls, and Calter's sculptures sometimes function as working sundials or sun calendars.

|

Slide 22-05: Armillary VII

Calter Photo |

Slide 22-06: Sun Disk, Moon Disk

Calter Photo

The Nine Circles of Heaven

But enough of this murky sublunary world where the air thick and dirty. Lets have a space odessy to the translunary world where the ether is clear and pure, to the celestial and the super-celestial spheres, the nine circles of heaven.

|

Slide 10-15: DI PAOLO: Dante leaving the Earth

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 74 |

On our trip lets follow in the footsteps of Dante and Beatrice, in his Paradiso, shown here leaving the earth for the moon.

Dante's Paradiso

Paradiso is one book of the Divine Comedy written by the poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). It was started about 1307 was completed shortly before his death. It is an allegorical narrative of the poet's imaginary journey through hell and purgatory, guided by Virgil, who is, to Dante, the symbol of reason.

|

Slide 10-13: DELACROIX: Dante and Virgil

Clark, Kenneth, The Romantic Rebellion. NY. Harper, 1972. p. 202 |

Dante is guided through the circles of heaven by Beatrice, a woman he met in 1274, and whom he loved and exalted in La vita nuova (The New Life) and in Paradiso.

|

Slide 10-12: Dante and Beatrice

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 183 |

In each realm the poet meets mythological, historical, and contemporary personages, each symboliizing a particular fault or virtue, each receiving the appropriate punishment or reward. In his Paradiso he conceived of heaven as a gigantic rose, built of circular rings of light simialr to the rose window of a Gothic cathedral.

Nine Ranks of Angels

|

Slide 10-8: HILDEGARDE VON BINGEN. Nine Ranks of Angels

Fox, Matthew, Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen. Santa Fe: Bear, c 1985. p. 74 |

When we left the world of people we entered the realm of the angels, supposedly arranged in three ranks of three -- a triple trinity -- shown here in Hildegard von Bingen's Nine Ranks of Angels.

Lowest Heirarchy:

| Angels | Moon |

| Archangels | Mercury |

| Principalities | Venus |

Middle Heirarchy:

| Powers | Sun |

| Virtues | Mars |

| Dominations | Jupiter |

Upper Heirarchy:

| Thrones | Saturn |

| Cherubim | Fixed Stars |

| Seraphin | Emperian |

This arrangement is from a sixth-century book, The Celestial Hierarchy, ascribed to the neoPlatonist known as the Pseudo-Dionysius. (This is not the fun Dionysius of Greek Mythology, the god of wine, orgies, Phallicism, and dorm parties.)

Circle 1. The Moon

The Illustrations for Paradiso

We'll look at two sets of illustrations for Paradiso; the ones in color are by the Sienese artist Giovanni di Paolo, done about 1445, and the monochrome etchings are by Gustav Doré, done in the 1900's. Occasionally we'll have illustrations of the same passage by the two artists, like these, where Dante and Beatrice converse with Piccarda dei Donati and the Empress Constanza, who broke their vows and thus occupy the lowest sphere of heaven.

|

Slide 10-17: Donati and Costanza

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 182 |

|

Slide 10-16: DI PAOLO: Donati and Costanza

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 76 |

We'll see that the di Paolo illustrations are generally more specific and more literal than Doré's. They refer to a specific passage in the allegory, while the Doré pictures can usually go anywhere in the story.

Cigoli's Immacolata

|

Slide 10-27: TIEPOLO:

Immaculate Conception, 1767.

Fisher, Sally. The Square Halo. NY: Abrams, 1995. p. 53 |

A popular art motif featuring the moon is the Virgin standing on the moon, usually wearing a crown of stars.

And a great portent appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of stars.

Notice the radiance coming from her body, showing her clothed in the sun.

|

Slide 10-25: CIGOLI' Immocolata

Edgerton, Samuel. The Heritage of Giotto's Geometry. p. 252 |

But we're particularly interested in this version, done in 1612 by Cigoli. Note the mandorla, the nine celestial circles, and the dome as a model of the heavens. But especially look at the moon. For the first time it is shown pock-marked.

|

Slide 10-26: Galileo's Moon Drawings

Edgerton, Samuel. The Heritage of Giotto's Geometry. p. 241 |

Why? It turns out that Cigoli was pals with Galileo. Quoting Panofsky,

". . . the painter, as a good and loyal friend [to Galileo] paid tribute to the great scientist by representing the moon under the virgin's feet exactly as it had revealed itself to Galleo's telescope -- complete with . . . those little . . . craters which did so much to prove that the celestial bodies did not essentially differ . . . from our earth.

This may not seem like a big deal now but it defied convention and church doctrine that showed the moon either as a crescent or as a perfectly smooth orb, perfect and flawless as the person standing on it.

Moon Gods & Symbols

|

Slide 10-18: CORREGIO: Diana

Cayley, p. 63 |

|

Slide 4-8: The White Goddess

Graves Cover |

Of course, the moon had associations long before Christianity, like the moon goddesses Isis and Selene, and the triple goddess of the New, Full, and Old Moon, goddess of Birth, Love, and Death.

Angels

|

Slide 10-11: DELACROIX: Jacob Wrestling with an Angel

Clark, Kenneth, The Romantic Rebellion. NY. Harper, 1972. p. 220 |

Note that the moon has the lowest kinds of angels who do the grunt work, TV series, sell cellular phones, and wrestling with earthlings like Jacob.

Circle 2. Mercury

|

Slide 10-35: Mercury

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 87 |

Lets now head for Mercury, shown by di Paolo as a golden disk. Mercury, naked, stands surrounded by seven heavenly intelligences. Humanity, represented by the four youths, are being guided by both the Old and New Testaments.

Archangels

Mercury is the sphere that has the most interesting rank of angels, the archangels. There are only three, Raphael, Gabriel, and Michael. Raphael appears in the Old Testament Apocrypha Tobit, in some tale involving a fish, as in this drawing by Rembrandt.

|

Slide 10-37: REMBRANDT: Tobias and Raphael

Ward, Roger. Durer to Matisse - Exhibition Catalog. Kansas City: Nelson, 1996. p. 101 |

Gabriel is the archangel of the Annunciation, shown in this painting by Fra Angelico, one of the best portrayers of the annunciation.

|

Slide 10-39: FRA ANGELICO: Annunciation

Hartt, Frederic. Italian Renaissance Art. NY: Abrams, 1994. p. 14 |

But the superstar of the archangels is Michael from Revelations. Michael is often shown banishing Lucifer and the rebellious angels to hell.

|

Slide 10-41: BLAKE: Michael

Clark. Romantic Rebellion, p. 156 |

Circle 3. Venus

|

Slide 10-35: Venus with Cupid and Amor

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 97 |

On to Venus, where di Paolo shows her with two sons Cupid and Amor.

|

Slide 10-36: Talking to Charles Martel

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 208 |

|

Slide 10-37: DI PAOLO: Talking to Charles Martel

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 98 |

Here we have another direct comparison of pictures by the two artists, showing one Charles Martel who is telling Dante the story about how he lost Sicily.

Venus Coelestis & Venus Vulgaris

|

Slide 10-38: BOTTICELLI: Birth of Venus Slide # 1055

American Library Color Slide Company p. 187 |

There are actually two Venuses, discussed in Plato's Symposium, Celestial Venus and Earthly Venus. The two Venuses correspond to the notion of Sacred and Profane love, a big topic in the Renaissance, shown here in a painting by Titian.

|

Slide 10-39: TITIAN: Sacred and Profane Love

Christiansen, Keith. Italian Paintings. NY: Levin Assoc. 1992. p. 194 |

Circle 4. The Sun

|

Slide 10-42: DI PAOLO:

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 102 |

Here Dante and Beatrice reach the sun, shown by di Paolo as a golden wheel sending golden rays to the landscape below. The Sun, located in the middle of the orbs, with three lesser above and three below, like the heart in the middle of the body, or a wise king in the middle of his kingdom.

Sun Gods & Symbols

|

Slide 10-44: Aztec Sunstone

Dia.: 11' 2", wt.: 24 tons Argüelles, José and Miriam. Mandala. Boston: Shambhala, 1985. p. 37 |

Recall that the circle was often used to symbolize the sun, and that Sun worship is one of the most primitive forms of religion, with early man often distinguishing between the triad of rising, midday, and setting sun, like the three Egyptian sun gods; Horus, the rising sun; Ra or Rê, themidday sun; Osiris, the old setting sun.

Circle 5. Mars

|

Slide 10-47: Cross

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 242 |

|

Slide 10-48: DI PAOLO: Cross

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 126 |

Lets zip by Mars, the red Planet, shown in that color by di Paolo. Here we see two different representations of the cross made up of eight holy warriors, Joshua, Judas Maccabaeus, Charlemagne, and more.

Circle 6. Jupiter

|

Slide 10-53: Eagle

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 266 |

|

Slide 10-54: DI PAOLO: Eagle

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 131 |

For Jupiter we have another good comparison of the illustrations by Paolo and Doré. Here the souls of the Just Rulers form into an eagle symbolizing divine justice and imperial authority, and speak with a single voice from its beak.

Circle 7. Saturn

|

Slide 10-57: DI PAOLO:Saturn

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 137 |

|

Slide 10-56: GOYA: Cronos devouring Children

citation |

On to Saturn, shown as an old man with a sickle. Saturn often represented father time because of the confusion between Chronos, the Greek word for time, and Kronos, the Roman for Saturn.

The sickle may represent the grim reaper, eventually mowing down every living thing, or the instrument he used to castrate his father Uranus. Saturn is often shown devouring his children, signifying that "sharp-toothed" time devours whatever he has created.

Circle 8. The Fixed Stars

|

Slide 10-58: DI PAOLO: Stars

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 145 |

As they rise to the fixed stars, Dante and Beatrice look back and see the seven planets beneath them; the sun, lower left, a scarlet figure in a flaming chariot, to the right the moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn, arranged by the days of the week.

|

Slide 10-62: St. John Questions Dante

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 300 |

|

Slide 10-63: DI PAOLO: St. John Questions Dante

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 158 |

Here's another direct comparison between Dore and di Paolo, where St. John questions Dante on the subject of Charity, one of the three ecclesiastical virtues.

Cherubim

|

Slide 10-64: Cherubim. S. Marco Cupola

Demus, Otto. The Mosaic Decoration of San Marco, Venice. Chicago: U. Chicago, 1988. P. 44A. |

We haven't seen any angels since we left the archangels. Each sphere has its own type, but they have not been depicted by artists. But here in the fixed stars we have the Cherubim, little babylike creatures. They are probably recycled classical putti .

Sometimes only winged heads are shown. Others are shown with several sets of wings, often in the shape of a cross.

The Zodiac

|

Slide 10-67: Fountain of Neptune, P. della Signoria,

Florence

Calter Photo |

|

Slide 10-68: Torah Crown detail, c. 1770

Jewish Museum (New York, N.Y.), Treasures of the Jewish Museum. NY: Universe, 1986. p. 103 |

Stars as art motifs are found mostly in the zodiac, and we find these everywhere.

The Stars in Painting

|

Slide 10-69: TINTORETTO:

Origin of the Milky Way, c. 1577

Kent, p. 21 |

The star-filled sky has fascinated artists. Tintoretto's painting shows a rather literal explanation for the Origin of the Milky Way. Edvard Munch did two Starry Nights, and, of course, Van Gogh made another painting with the same title.

|

Slide 10-74: MUNCH:Starry Night, 1893. (At Getty)

Munch, p. 106 |

Circle 9. The Primum Mobile

|

Slide 10-75: Primum Mobile

Dante, The Divine Comedy. Ill. Gustave Doré. London: Cassell. p. 310 |

|

Slide 10-76: DI PAOLO: Primum Mobile

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 162 |

We now come to the last sphere, the primum mobile, or first moved, the sphere which dictates the motions of the other spheres. Here it is shown by di Paolo as a ring of golden light framing a mappamondo in the center of which is the figure of Christ.

|

Slide 10-79: MANTEGNA: Assention,

showing seraphim

Campbell, Joseph, with Bill Moyers. The Power of Myth. NY: Doubleday 1988. figure 19 |

The angels assigned to this sphere by Dionysius are the seraphim, usually depicted like cherubim, but are red.

The Empyrium

|

Slide 10-82: DI PAOLO: Cosmic Rose

Pope-Hennessy, John. Paradiso. The Illuminations of Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo. NY: Random, 1993. p. 177 |

We finally reach the Empyrian, the highest heavenly realm, supposed to be composed by a kind of sublimated fire, the uppermost Paradise, the heaven; the seat of God. The image that dominates the final Cantos of Paradiso is the cosmic rose, shown by di Paolo as an actual rose, with nine angels and the Trinity.

And in the very last paragraph of The Divine Comedy, at the end of this fantastic journey down to hell and back, and through purgatory, and up through the circles of heaven, what does Dante talk about? Beatrice? God? No. He talks aboutgeometry.

As the geometer who attempts to measure the circle

and discovers not . . . the principle he wants,

So was I at that new sightI wished to see how the image conformed to the circle

[but] here my power failed,

but my desire and my will were revolved,

like a wheel that is evenly moved

by the love which moves the sun and the other stars.

So we end our journey to the heavens with love and with geometry; what more could anyone who loves math ask for?

Reading

Dixon, Laurinda. Giovanni di Paolo's Cosmology. Art Bulletin, Dec. 1985, pp. 604-613

Janet Saad-Cook. Natural Phenomena, Earth, Sky, and Connections to Astronomy. Leonardo, V.21, No. 2, 1988, pp. 123-134

Vitruvius, Book IX. Dover Edition pp. 251-277.

Panofsky, Studies in Iconology, pp. 129-169

Lippincott, Kristen. Giovanni di Paolo's "Creation of the World." Burlington Mag. 1990, pp. 460-468

Partridge, Loren. The Room of Maps at Caprarola, 1573-75. Art Bulletin, Sept. '95, pp. 413-444

Pacholczyk, Josef. Music and Astronomy in the Muslim World. Leonardo, V29, No. 2, pp. 145-150, 1996

Tillyard, The Elizabethan World Picture. pp. 37-82

Ostrow, Steven. Cigoli's Immacolata and Galileo's Moon. Art Bull. June '96, pp. 218-235.

Dante, Paradiso

Pope-Hennessey, Paradiso

Pseudo-Dionysius, Smith